- Contact us:

- 020 8203 6288

- info@chinmayauk.org

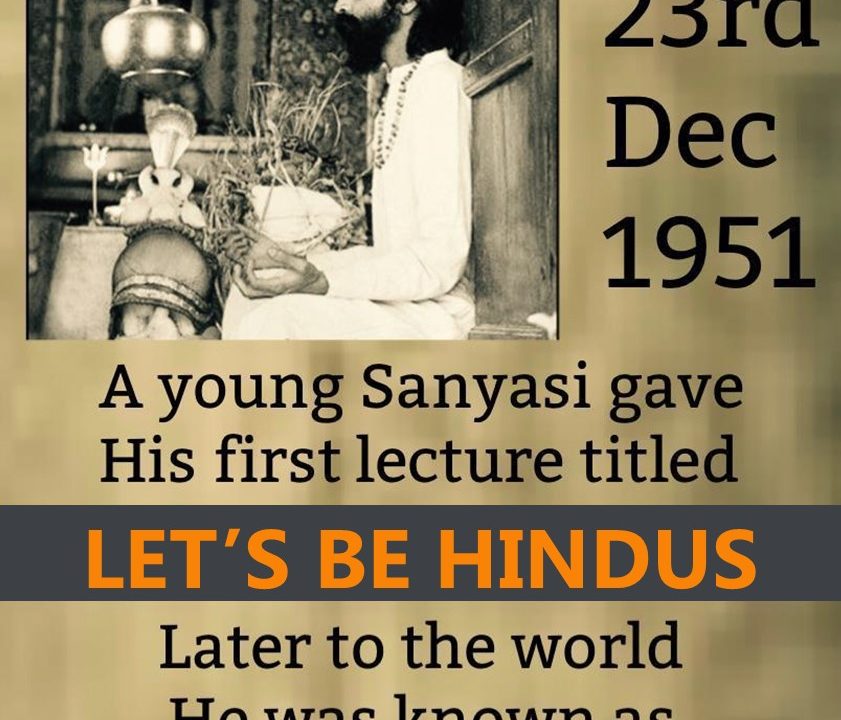

Immortal Values

Let us be Hindus

30th December 2013Mission and Vision

30th December 2013The great religious masters of India, using their own ingenious efforts, have time and again revived the philosophical and religious values for which India stood and thereby arrested the deterioration of the culture.

When culture deteriorates there is an increase in barbarity and immorality in the country and its philosophy is misinterpreted, leading to confusion and chaos among its people. This, in short, is more or less the sad condition of the present world. The need of the hour is to arrest forthwith the deterioration by reviving the great philosophical and religious values of life. In no other literature in the world have these values been so beautifully and exhaustively dealt with as in the sacred books of India.

In this context we may note the following advice given to the students by the Rishi of the Taittiriya Upanishad : The practice of what is right and proper is fixed by the scriptural texts; it is to be followed along with reading the texts oneself and propagating the truths of the same. (“Truths”: this means that practising in life what is understood to be right and proper is to be pursued along with regular studies and preaching.)

This Upanishadic passage closely parallels the corresponding function that we have in our colleges today, which goes by the term, “Convocation Address”. The students of the Gurukula are given some key ideas on how they should live lives dedicated to their culture, consistent with what has been taught to them as the goal and way of life.

More than Just Facts

It must be the duty of the educationists to see that they impart to the growing generation not merely some factual knowledge or some wondrous theories but also ideals of pure living, and training in how to live those ideals in practical life. In short, the secret of a sound culture is crystallized in this convocation address; this portion is more exhaustively amplified in the section that follows the address.

In this section the teacher presents twelve immortal ideas of living and rules of conduct. An equal number of times he has insisted that the student continue his study of the scriptures and propagate the immortal ideas of his culture all through his life. In these passages, we find that the brilliant students are repeatedly commissioned to continue their study and be preachers throughout their lifetime. The Upanishadic style lies in its brevity. Use of even a syllable more than the minimum required is considered as a great sin; yet, here we find in a small section twelve repetitions of the same idea; study (swadhyaya) and discoursing upon the Veda with a view to making others understand (pravachana).

For this missionary work the Rishis never saw any necessity in organizing a special class of teachers. The preaching activity was built into the duty of every householder. In the pursuit of his vocation, the householder was not asked to spare any special time or to sacrifice his duties either towards himself or towards his own children, the society, the nation or the world. But while emphasizing the need to pursuing his duties at all these levels, the Rishis asked him to keep continuously in touch with the scriptures and to preach the same truth to others.

The great qualities that the teacher has insisted upon are:

(a) The practice of what is right and proper as indicated in the scriptures (ritam);

(b) Living up to the ideals that have been intellectually comprehended during the studies (satyam);

(c) Aspirit of self – sacrifice and self – denial (tapas);

(d) Control of the senses (dama);

(e) Tranquillity of the mind (sama);

(f) Maintenance of a charitable and ready kitchen at home in the service of all deserving hungry fellow beings (agni);

(g) Practice of concentration and ritualism through fire worship as was in vogue in the society of those days; and

(h) Doing one’s duty towards humanity, towards one’s children and grandchildren and towards the society.

Continuing the “Convocation Address”, the teacher says: Having taught the Vedas, the preceptor enjoins the pupil: “Speak the truth, do your duty, never swerve from the study of the Vedas; do not cut off the line of descendants in your family, after giving the preceptor the guru dakshina. Never deviate from the truth, never fail in your duty, never overlook your own welfare, never neglect your prosperity, never neglect the study and the propagation of the Vedas.”

After the studies, before the students are let out to meet their destinies in their independent individual life as social beings, the teacher gives his exhortation, which comprises, we might say, “Vedanta in practice”.

Relationship to Society

Satyam vada, “Speak the truth”: Truthfulness consists mainly in uttering a thought as it is actually perceived, without hypocrisy or any vulgar motive to do injury to others. Truthfulness in its essential meaning is the atunement of one’s thoughts with one’s own intellectual convictions.

Having developed this quality of truthfulness, where should one apply it? As if anticipating such a doubt in the student, the teacher says, dharmam chara. Dharma is a Sanskrit word that has no corresponding word in English. We may, for our convenience, but not to our full satisfaction, translate dharma as “duty”.

Hinduism is built upon duties and responsibilities, not on rights. A culture built upon duties recognizes the right to do one’s duty as the fundamental privilege in life. A generation that understands such a culture gets trained to demand of life ample chances to fulfil its duties. Duty, therefore, develops the spirit of giving, not the lust to hoard or the anxiety to keep.

The sequence of thoughts — “After giving the preceptor his fees, do not cut off the thread of progeny” — implies a healthy suggestion as how best to plan one’s life. After finishing your education, first of all become economically independent; learn a trade, create a market, assure a comfortable income. Then, as the next duty in life, marry and maintain the line of descendents in the family. This is followed by a series of warnings not to swerve from truthfulness, duty, personal welfare and prosperity. The Rishi advised the students to be prosperous so that they would be able to serve others in selfless charity. It is reasserted that we must pursue the study of the scriptures and make it a life’s mission to spread those truths among ourselves with a burning, irresistible missionary zeal.

Continuing the advice, the teacher says: Never swerve from your duties towards gods and towards the departed “souls” (manes). May the mother, father, preceptor and the guest be to thee a god.

Relationship to the Teacher

Philosophy is a subjective science, and its blessing can be gained only by actually living it. Apart from its logic and reason, the theory must have the dynamism of the teacher behind it to inspire the students at all times. If this reverence and respect for the teacher are not there, the moment suspicion and doubt creep into our minds regarding the purity and sincerity of the teacher, the philosophy that is declared becomes immediately impotent in our hearts. Therefore, the teacher says, “Follow only the irreproachable qualities in us.” Wearing the look of the ordinary and behaving as any ordinary mortal, these men of perfection faced their students. This, in fact, was the secret of their success in spreading the transcendental wisdom among people living amid life’s conditions in their day – to – day existence. The idea of the advice to students was that you must be all ears and eyes when the wise talk, and not be full of noise and tongue. When such teachers discuss, there are plenty of ideas that one must try to absorb, discuss later on and assimilate properly.

Practising Charity

Continuing the address to the students, the Rishi adds: Gifts should be given with faith: they should never be given without faith; they should be given in plenty, with modesty and with sympathy.

Hinduism recognizes the householder’s existence only as a necessary training in curbing his animalism and purifying him for the greater heights of spirituality. Cultural perfection is the goal. Ultimately the individual was valued upon the spirit of sacrifice he could show toward the finite, when the call of the Infinite reached him. Naturally, therefore, the teacher has to give some instruction as to how charity can best be practised. Therefore, charity is acceptable only when it toes the line with our own independent intellectual beliefs and convictions.

Indiscriminate charity is not acceptable to the science of Vedanta, which is not trying to cultivate fruit trees. Its aim is to cultivate the thinking animal called “man”. Therefore, the Rishi pointedly condemns the opposite idea by the positive declaration. “Gifts should not be given without faith.” Every benefactor has the right, even the duty, to inquire into the righteousness of the cause he is trying to patronize. It is said that having come to judge a cause to be deserving, give it your entire patronage: “Give in plenty; with both hands, give.” However, charity can bring to us the feeling of egoism and vanity. These are avoided by instructions to give with modesty. Charity constricts the heart and obstructs human growth if it is not honeyed with the spirit of love and the joy of identification.

Proper Conduct

Coming to the end of the “Convocation Address” given to the students, the Rishi says: Now if there should arise any doubt regarding your acts or any uncertainty in respect of your conduct in life and with regard to those who are falsely accused of some crime, you should conduct yourselves exactly in the same manner as do the brahmanas there, who are thoughtful, religious, not set on by others, not cruel, and are devoted to dharma.

An ideal Brahmin should be one who is not set on by others. He must not be cruel. He must be a self – dedicated champion of the greater values of life as explained in the immortal scriptures. Such men of dedicated life, firmly established in their ideas and stoutly independent, are the true sons of the Hindu culture, and the student is asked to follow them whenever there is a doubt regarding either action or conduct.

The above passages, starting with satyam vada, consisting of twenty – five items and divisible into six waves of thought, constitute the sacred commandments of Hinduism. The waves of thought as indicated in this section are advice regarding (1) the individual himself, (2) his relationship with others, (3) his right action in the world, (4) his attitude toward the eminent men of culture, (5) the laws of charity, and (6) his duty to follow the eminent living men of his own times.

In the seventh wave of thought, the teacher concludes by saying that these commandments are to be followed diligently by every intelligent seeker who lives a life for a higher cultural purpose — more than mere worldly ambitions and secular activities.

In short, over the shoulders of the students, as it were, the Rishi is addressing the entire community to follow these commandments and bring about the perfect cultural and spiritual unfoldment in themselves and in the society.